What is Ranked Choice Voting (RCV)?

This November, Portland will hold its first city election using Ranked Choice Voting (RCV), allowing voters to rank candidates on the ballot instead of marking one choice.

RCV is an umbrella term for multiple voting methods that use ranked ballots. Portland will use one form of RCV to elect the mayor and the auditor, and another to elect the city council.

From binary to multiple choice.

Previously, Portlanders could only vote for one candidate per contest. In the primary election, a candidate could win outright by securing a majority of the vote. If no candidate reached a majority, the two top vote-getters would advance to the general election for a runoff. To illustrate, this happened in the 2022 primary election, when incumbent Jo Ann Hardesty failed to secure a majority. Hardesty and the runner-up Rene Gonzalez, who secured 23% of the vote, proceeded to a runoff, where Gonzalez won the seat.

As of this year, Portland has eliminated primary elections for city offices. All candidates will instead appear on the November ballot, and winners will be determined via ranked choice voting.

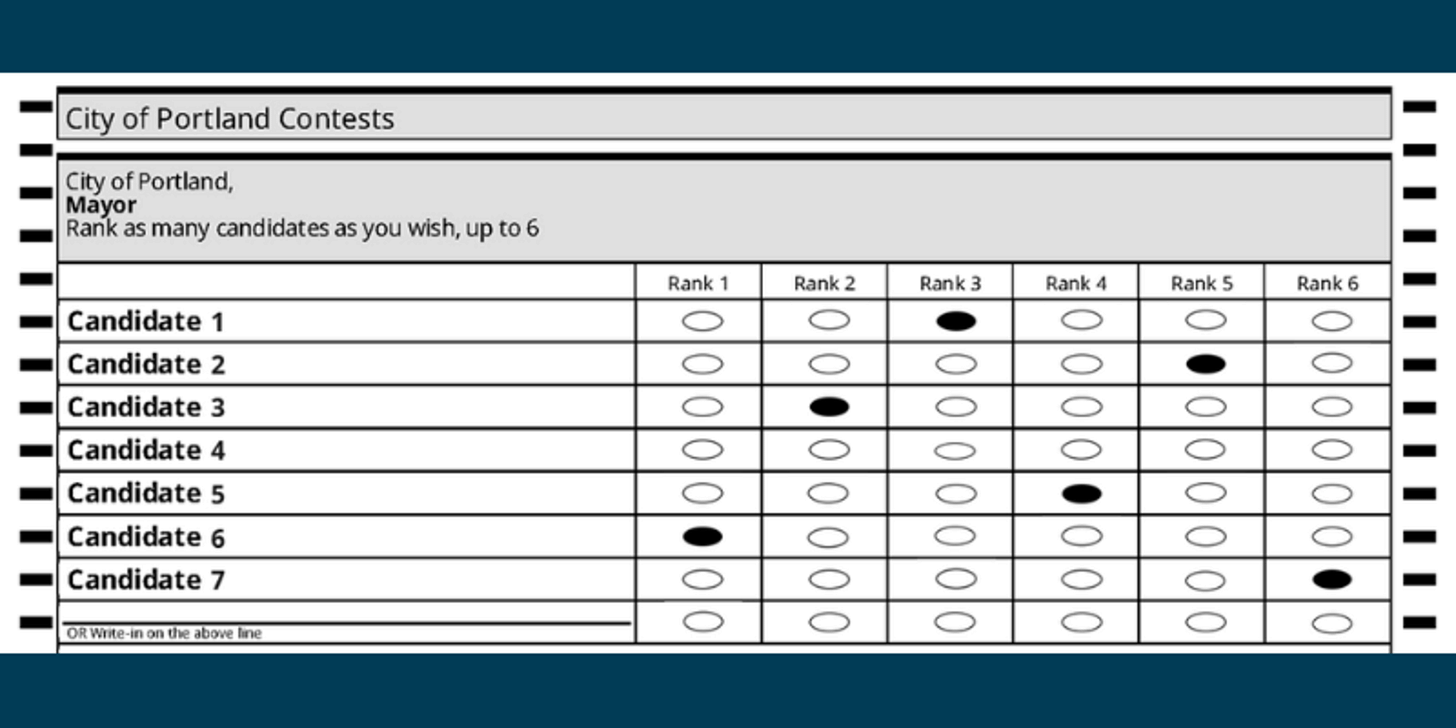

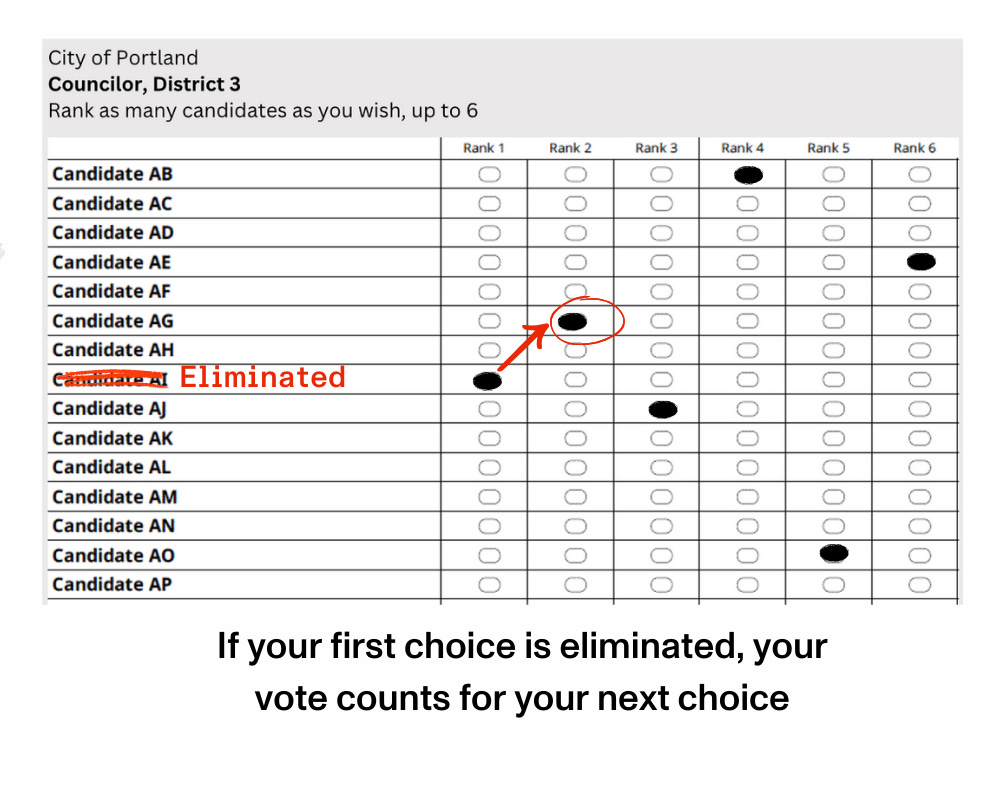

The new ballot allows Portlanders to rank candidates from one to six. The first ranking indicates your top choice. Subsequent rankings tell the vote tallying system how your vote may be moved if your first choice is eliminated. By gathering this information upfront, ranked choice voting eliminates the need for separate primaries or runoff elections.

Electing the mayor and auditor.

In elections with a single winner, such as the race for Portland Mayor, candidates must secure a majority—at least 50% plus one vote—to be elected. If a candidate reaches that threshold with first-choice votes alone, they win the election outright.

If no candidate achieves a majority, the lowest-scoring candidate is eliminated. Votes for the eliminated candidate are then transferred to voters’ second choices in the order indicated on their ballot. This process repeats, with votes shifting to lower-preference rankings as candidates are eliminated, until a majority-winner emerges.

Electing the council.

In Portland’s council elections, the objective is not to elect a majority-winner, but to identify the three candidates with the broadest support across the district.

Council elections use a form of ranked choice voting known as single transferable vote or proportional ranked choice voting. This method sets a specific threshold that candidates must meet to be elected. In Portland’s district elections, that threshold is 25% plus one vote.

When a candidate reaches the threshold, they win a seat. Portland’s council elections have three seats available, so if three candidates reach the threshold, they are elected. However, if the first round of counting doesn’t result in three winners, rankings are used to identify the the candidates with the most support.

If one candidate gets more votes than they need, and there are still seats left to be filled, the winning candidate’s excess votes (also knowns as surplus votes) are redistributed to the next-ranked candidate on each ballot. This means that if your first choice wins with a surplus of votes, your next choice could get a boost. The size of the boost depends on how large the surplus is. For example, if your first choice wins 10% more than they need, 10% counts for your next choice on the ballot.

If there are still seats remaining after first-choice votes have been counted and surplus votes redistributed, the system eliminates the lowest-ranked candidates and transfers their votes to voters’ next choices until three seats have been filled.

Understanding proportional representation.

Single transferable vote, or proportional ranked choice voting, results in proportional representation. This electoral system elects multiple seats to mirror the often-diverse preferences of voters within a voting district.

To illustrate the contrast between Portland’s former winner-takes-all system and proportional representation, consider the 2022 primary election for Position 3 on the Portland City Council.

In this election, the progressive incumbent Jo Ann Hardesty received the largest vote share at 44%. Rene Gonzalez and Vadim Mozyrsky, who had more centrist platforms, split most of the remaining votes between them. Since Hardesty did not achieve an outright majority, she and Rene Gonzalez advanced to a runoff in the general election, where Gonzalez won with 53%. The result? The centrist voters got all of the representation, and Hardesty’s more progressive supporters got none.

How would the outcome have differed with proportional ranked choice voting?

For starters, the results would have been delivered in a single election, without the need for a separate runoff. Hardesty would have been elected outright by surpassing the election threshold of 25% plus one vote. Additionally, her surplus of approximately 19% would have been redistributed to voters’ next choices.

Given how close both Gonzalez and Mozyrsky got to the threshold, Hardesty’s surplus likely would have propelled both of them across the finish line. If either candidate had still fallen short, lower-scoring candidates would have been eliminated, and their votes redistributed until three candidates reached the threshold. Most likely, Hardesty, Gonzalez, and Mozyrsky would have become colleagues on the council.

The election outcome would have reflected voters’ preferences, with a majority favoring Gonzalez’ and Mozyrsky’s centrist views, but with a sizable minority supporting Hardesty’s more progressive stance.

To rank or not to rank?

Ranking your ballot is optional, not mandatory. If you choose not to rank, your vote simply stays with your first choice. However, ranking your ballot has benefits, such as the ability to support more than one candidate, and mitigating the so-called spoiler effect, where two similar candidates split the vote, unintentionally contributing to the victory of a less popular candidate.

A common criticism of ranked choice voting is that it places a greater burden on voters to make decisions. While educating yourself about candidates can feel daunting, investing time in understanding candidates’ platforms can significantly improve representation. A San Francisco study found that voters who consulted voter guides to inform their rankings made choices that more closely matched their personal politics than voters who used no supplemental information.

Whether you decide to rank candidates or not, think of it this way: Just fifteen minutes of research could save you four years of representation by someone whose values don’t align with your own. Visit Rose City Reform’s candidate tracker for concise information about all of your choices this November.

Thanks for reading Rose City Reform! Subscribe for free to support my work.