The trouble with boring voting methods.

If learning about the Charter Commission's reform measure weren't so darn boring, voters would be better informed by now.

Ever feel like the debate about Portland’s charter reform measure is all fight and no information?

That’s because the most contested part of the ballot measure is also the most boring part.

But don’t you want to know what all the fuss is about?

This week I’m piloting a new type of content designed to make you look like the smartest person in the room whenever charter reform comes up. I’m calling it… drum roll… Charter School.

Today’s subject is single transferable vote (STV). Sound boring? Well, tough luck! Here we are, two months from the November election and nary a soul knows what the heck STV means.

If you’re a Portland voter, you’ll soon be voting on whether to adopt it. And just so you know, it’s one of the main things the yes and no campaigns are fighting about.

If you want to understand Portland’s charter reform measure, you must first understand single transferable vote.

Two voting methods wrapped in one package.

Last week I wrote about ranked choice voting, a voting method that’s becoming increasingly popular nationwide. Perhaps you read about it in the news lately as pundits theorized whether ranked choice voting caused Sarah Palin’s recent defeat in Alaska.

This November, five jurisdictions in the Pacific Northwest will vote on whether to adopt ranked choice voting. Portland is one of them.

But here’s the kicker: Portland’s charter reform measure contains two voting methods, not one.

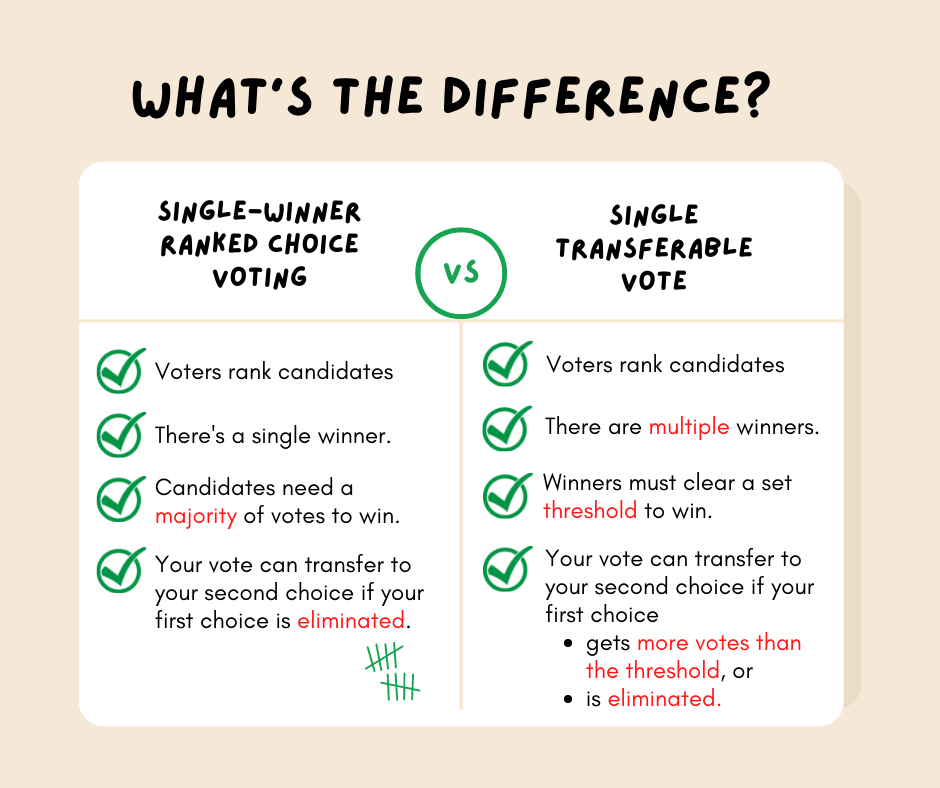

They both use ranked ballots, but they’re not the same.

The popular form of RCV elects one seat.

When people talk about ranked choice voting in the United States, they generally mean single-winner ranked choice voting.

Single-winner ranked choice voting elects one seat. Only one winner emerges. It’s by far the most common form of ranked choice voting in America. In Alaska’s closely watched special election, it was one seat in the U.S. House of Representatives that was up for grabs.

Under the Charter Commission’s proposal, this voting method would be used to elect Portland’s mayor and auditor.

With STV, we can elect three.

But what about Portland’s City Council?

The charter reform measure would divide Portland into four city council districts that would each elect three seats.

Would those seats also be elected using ranked choice voting?

Yes. But a different kind.

City Council would be elected via single transferable vote (STV). It’s also referred to as proportional ranked choice voting, or multi-winner ranked choice voting.

STV is popular in countries like Ireland, Scotland and Australia. In the United States, several jurisdictions used it during the first half of the 20th century. A handful of small U.S. jurisdictions, like Cambridge, MA and Eastpointe, MI, use STV today.

STV lowers the threshold for winning a seat.

Unlike ranked choice voting that produces a single winner, STV doesn’t require a majority to win a seat. Candidates must instead clear a threshold – or a quota – to win one of multiple seats.

How high is the threshold? That depends on the number of seats to be filled.

In Portland’s 3-seat district elections, the threshold would be 25%+1. That’s because the threshold is always the smallest possible percentage needed to secure a seat. In a 3-seat election, that’s 25%+1.

Hey! Stay awake! We’re more than halfway there!

STV winners only keep the votes they need.

In STV elections, voters cast only one vote. But by ranking candidates on the ballot, they tell the voting machine how their vote is allowed to be moved. You may remember that in ranked choice voting elections, votes can transfer when a voter’s first choice is eliminated.

With STV, votes can also transfer if a candidate gets more votes than they need.

Say what?

Remember the threshold? If a candidate receives additional votes after clearing the threshold – they don’t get to keep them.

Those additional votes – called surplus votes – transfer to voters' next choices on the ballot. The exact nature of this process varies between jurisdictions, and the charter reform measure doesn’t specify the particular mathematical process that would be used in Portland.

Read an expert prediction of how single transferable vote would work in Portland.

Even with lower thresholds, runoffs happen.

Although STV significantly lowers the threshold for getting elected, sometimes a runoff is necessary to fill all the seats.

Low-scoring candidates are eliminated from the bottom. If a voter checked an eliminated candidate as their top choice, their vote transfers to their second choice instead. This is not the same as voting twice. Your vote only counts for the candidate to whom it’s been allocated.

The process continues in rounds until all seats have been filled.

The end. Phew! You’re now free to go about your day with the satisfaction of knowing more about STV than all your friends combined.

What’s more, you might start to notice that the tension between the yes and the no campaigns largely comes down to – you guessed it – STV elections.

Despite its tediousness, STV evokes strong feelings.

As dry as it is, STV tends to inspire passion in its supporters. Many hold it as the gold standard of ranked choice voting. Proponents believe it’s a fairer and more representative way to elect a governing body because the majority isn’t the only voting group that can elect all the seats.

Meanwhile, opponents say STV is too complicated, doesn't translate well from European partisan elections to nonpartisan city elections, or gives outsized power to voting groups that aren’t supported by the majority.

That, dear readers, is entirely a matter of personal preference.

A decision that you, perhaps, are now better equipped to make because you sat through this excruciating exercise.

Unless you stopped reading after the first paragraph.

That’s the trouble with boring voting methods.

This post has been updated to reflect that Portland’s charter reform measure doesn't specify the way that surplus votes would be distributed to next-choice candidates.

Learn more about STV.

FairVote: How proportional RCV works.

Sightline Institute: How proportional representation gave American voters meaningful representation in the 1900s.

Jack Santucci for 3Streams: Ranked-choice voting didn’t solve our problems in the last century. And it won’t today.

Pew Research Center: More U.S. locations experimenting with alternative voting systems.